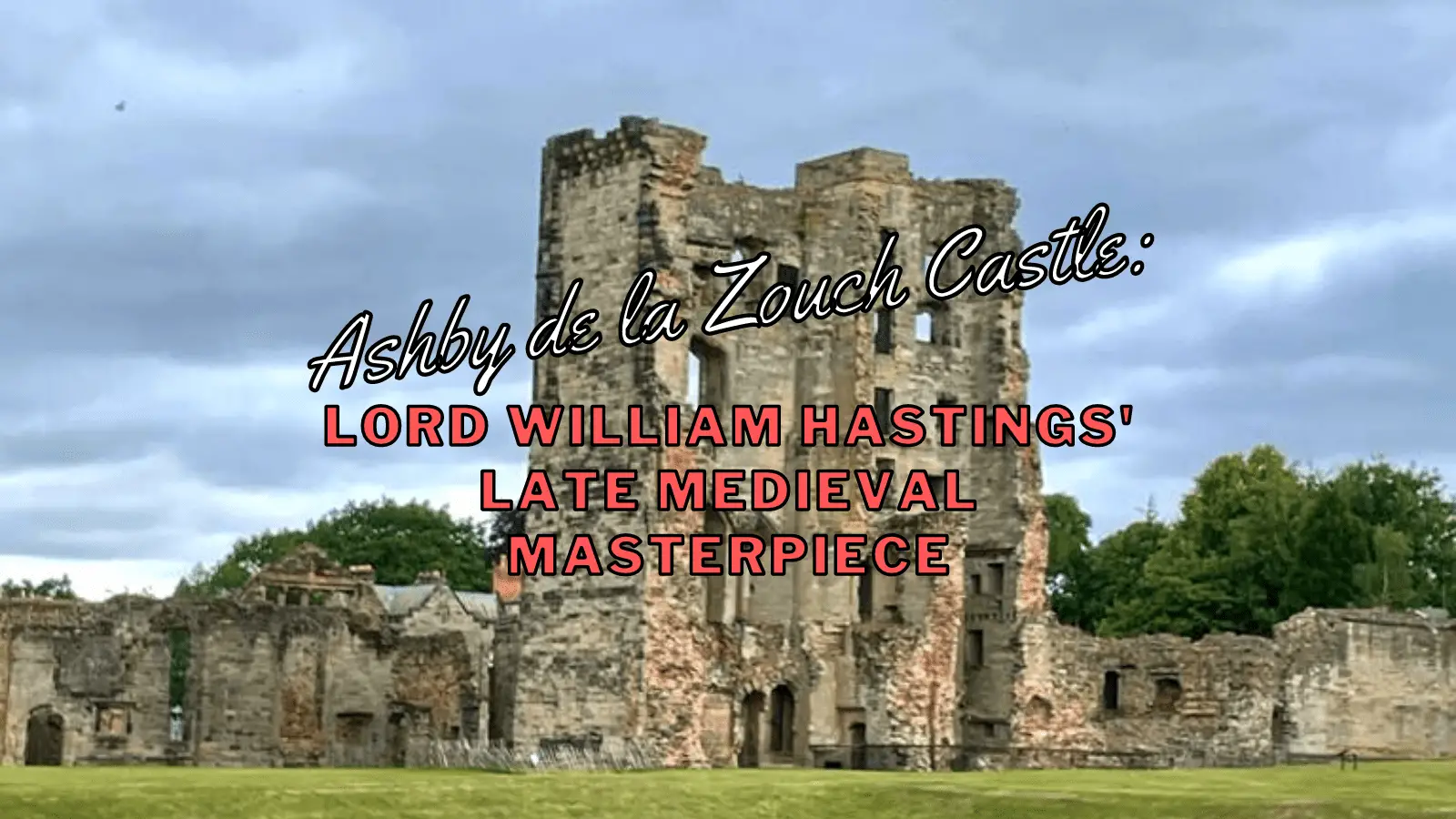

Ashby de la Zouch Castle: Lord William Hastings’ late medieval masterpiece

Standing in a 3,000-acre (1,200 ha) park is the ruined fortification of Ashby de la Zouch Castle in Ashby-de-la-Zouch, Leicestershire, England. Originally constructed on the site of an older manor house by William, Lord Hastings between 1472 and 1483, the castle was joined by two large towers and some smaller buildings over that time. Lord Hastings held indubitable power in England’s political arena in the late 1400s but never saw his grand design completed. On 13 June 1483, Richard, Duke of Gloucester had Hastings executed as an obstacle to his own royal ambition. The Hastings family continued to use the castle as their seat for several generations, adapting and improving the grounds and the castle and hosting royal visitors. The castle was a veritable star during both the Civil War when it was held for the king and in the pages of Sir Walter Scott’s novel Ivanhoe.

Centuries before its stardom, however, at the turn of the 11th century, the Earls of Leicester granted the land in return for military service to a family of Breton descent who bore the name ‘le Zouch’, which means ‘a stock’ or ‘stem’. William, Lord Hastings came by the land after the last direct heir to the Zouch inheritance passed away in 1399. At this time, Hastings was already remarkably wealthy and powerful thanks to his service to Edward IV. As such, he had reached virtual vice-regent status in Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, Leicestershire, and parts of Warwickshire and therefore needed a residence befitting his stature.

He used the vast acreages for hunting, and the architectural centrepiece of his creation in the form of the great tower was regarded as one of the largest structures of its kind in Britain. Hastings’ vision was of a castle with four towers set around its perimeter wall, but only one tower was realised, the kitchen tower. The lower two storeys of this kitchen tower featured hearths and cauldron rings, earning the cooking space its reputation as befitting a royal palace. The kitchen boasted its own well, a cellar below for kegs and the like, and a spacious winter parlour above, adequately heated by the kitchen fires. The broad kitchen hatch was used through which to serve the meals to the yard beyond.

The Great Tower was a testament to Hastings’ power and wealth, and even in ruins, holds stays as the architectural centrepiece of the castle. Hastings’ coat of arms remains vigilant in a few spots on the outside of the tower, not least of which is in an ornamental niche high above the door.

King George’s grandson Henry, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, was the jailer of Mary, Queen of Scots, when she was held at Ashby in November 1569. When George’s grandson Henry, the 5th Earl (1586–1643), had ownership of Ashby, the gardens were likely developed for entertaining royalty. The gardens are recognised as among the best-preserved and most important early Tudor gardens in the country. Records show the creation of a wilderness and the procurement of fruit, plants, and furniture for the property. “The wilderness” was, in fact, to be found beyond the gardens, planted with trees and incorporating a compartmented garden and ponds. The triangular “the Mount” took its position in the wilderness in the early 1600s. It is now used as a private residence.

Records of the gardens and orchards of Ashby go back as far as the 14th century, with evidence that the current gardens probably date back to 1530. They now occupy 2.0 acres (0.8 ha) with two sunken areas separated by a walkway.

Ashby was a Royalist base and played a crucial part in Royalist operations in the north and south throughout the English Civil War when Henry Hastings, the 6th Earl, occupied the property. He fortified the town and castle, and in 1644, the great tower was known as ‘Hastings’ stronghold’. Prominent Royalists were initially imprisoned within the castle buildings, but following Parliamentarian raids on the town, Hastings surrendered on 28 February 1646. He agreed to tear down his fortifications around the town, and the defences were demolished.

The end of the Civil War saw the Earls of Huntingdon residing elsewhere, but they never altogether abandoned Ashby. The widowed Countesses of Huntingdon used the surviving and restored buildings, including the medieval hall, as a dower house called Ashby Place. Selina, the wife of the 9th Earl, was among the last of the family to live here following her husband’s death in 1746. She lived to become a religious enthusiast and established the Calvinist sect in 1783, which was to be known as the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion. The last remaining Hastings Earl of Huntingdon, Francis, died in 1789 without having children. The estates passed by marriage to the Earl of Moira, Francis Rawdon, who was a soldier and imperial administrator.

Sir Walter Scott published his medieval romance Ivanhoe in 1819, setting a tournament scene at Ashby. Ashby’s resultant notoriety drew visitors wanting to see the castle ruins. Lord Moira’s agent saw to it that the ruins were transformed into a popular resort, after which, in 1824, the first guidebook to the town was published. Lord Moira permitted his son, John, to demolish Ashby Place and replace it with the gothic Ashby Manor, now used as a school.

The 1800s saw much reparation to the castle ruins, particularly the two towers. The state took over guardianship of Ashby de la Zouch in 1932. It has been under the care of English Heritage since 1983.