Eyam – The Plague Village of the Damned

The Derbyshire village of Eyam in the Peak District is nestled between Buxton and Chesterfield, north of Bakewell. It is home mostly to rural farmers, although its history is steeped in lead mining. Most significant, though, is its contribution to world health during the period around 1665. Up until then, it was much like all the other villages along England’s trade routes linking them to London. So what happened to make it one of the most significant villages in England in 1665?

The name Plague Village is an obvious clue as to the 800 residents of the time influencing the treatment and containment of the plague. This is the story…

Rose Cottage – Nine Members of the Thorpe Family died here.

Eyam’s resident tailor took delivery of a bundle of cloth from London in this auspicious year. There is nothing unusual about that apart from the fact that this delivery was particularly flea-infested. This brought about the onset of the bubonic plague, which ferociously took hold and spread throughout the village. The village rector, Reverend William Mompesson, imposed quarantine, and for 14 months, any movement in and out of Eyam was forbidden.

Plague Cottage – George Viccars, the first victim, died here on the 7th September 1665

Neighbouring villagers looked after the Eyam residents during what they regarded as a selfless act using what was called the boundary stone. This gritstone boulder in the fields between Eyam and Stoney Middleton had six holes drilled into the top. Benefactors put money into these holes to go towards feeding and medicating their quarantined neighbours.

Bagshaw House

- Richard, aged 11, died 11th September 1665

- Sarah, aged 13, died 30th September 1665

- John, the father, aged 45, died 14th October 1665

- Ellen, aged 23, died 15th October 1665

- Elizabeth, aged 21, died 22nd October 1665

- Alice, aged 9, died 22nd October 1665

- Emmot, aged 22, died 29th April 1666

- Elizabeth, (mother) who remarried, died 17th October 1666

- John Daniel, Elizabeth’s second husband died 5th July 1666

During this time the village contained the spread of the disease. But it did lose more than one-third of its 750 residents to the plague, with a total of 260 deaths. By the time the outbreak ran its course, it became evident that the village residents showed a genetically unique immunity to the deadly plague. Today, descendants of the surviving villagers still carry this natural immunity.

The village has celebrated this episode in its history ever since the plague’s bicentenary in 1866 by hosting Plague Sunday in Cucklett Delph on the last Sunday in August.

Before earning the name Plague Village, Eyam was the site of Roman lead mining. The coins found here are evidence of this, bearing the names of many long-dead Roman emperors. Visitors can see the remnants of stone circles, such as the Wet Withens stone circle on Eyam Moor. Ancient Earth barrows previously destroyed can also be seen on the moors above the village.

An Anglo-Saxon cross in Mercian style is housed in the churchyard. It is a Scheduled Monument dating back to the 8th century having been relocated from beside a moorland cart track. The complex carvings are intriguing and the cross is complete except for a section of its shaft.

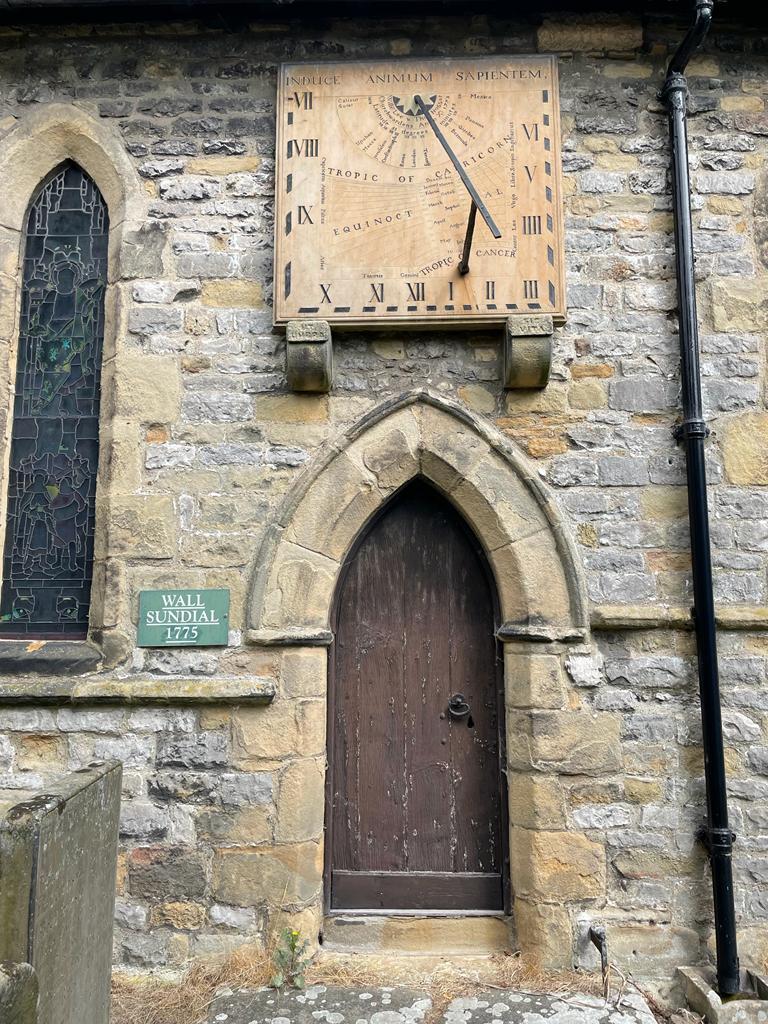

The parish church of St. Lawrence, still in use today, dates back to the 1300s. It does, however, go back even further, as can be seen by the Saxon font, a Norman window at the west end of the north aisle, and Norman pillars supported by Saxon foundations. A large sundial dated 1775 is mounted on an exterior wall.

Ancient custom saw the church rectors receiving one penny for every ‘dish’ of ore and twopence farthing for every load of hillock stuff. Historically, the rectors prove to be quite colourful. The Royalist Sherland Adams was imprisoned for giving tithes of lead ore to the King against the Parliament. A rich vein of lead discovered in the 1700s provided well for the Eyam residents. The area bears witness to 439 known mines, some under the village itself. The Ladywash Mine was the last to remain in operation, closing in 1979.

The village’s move in the 20th century from an industrial and mining industry to tourist based is notable by Roger Ridgeway’s statement that “a hundred horses and carts would have been seen taking fluorspar to Grindleford and Hassop stations. Until recently, up to a dozen coach loads of visiting children arrived each day in the village…”.

Places of Interest in and around Eyam, the Plague Village:

- Cucklett Delf hosted church services during the quarantine. It was believed that gathering outdoors in this natural amphitheatre was safer for the parishioners. The illicit sweethearts Emmott Sydall from Eyam and Rowland Torre from a neighbouring village, met here in secret, too. The two called to each other across the rocks up until Emmott Sydall was taken by the plague.

- Mompesson’s Well was used as a receptacle for neighbouring villagers to provide money and food to the quarantined Eyam villagers.

The Grave of Catherine Mompesson

3. Boundary Stone was used similarly to Mompesson’s Well during the quarantine.

4. Plaques on the cottages

5. Gravesites

6. Eyam Parish Church of St Lawrence in the heart of the village boasts the eighth-century Celtic Cross and a book bearing the names of inhabitants taken by the plague.

7. Eyam Museum