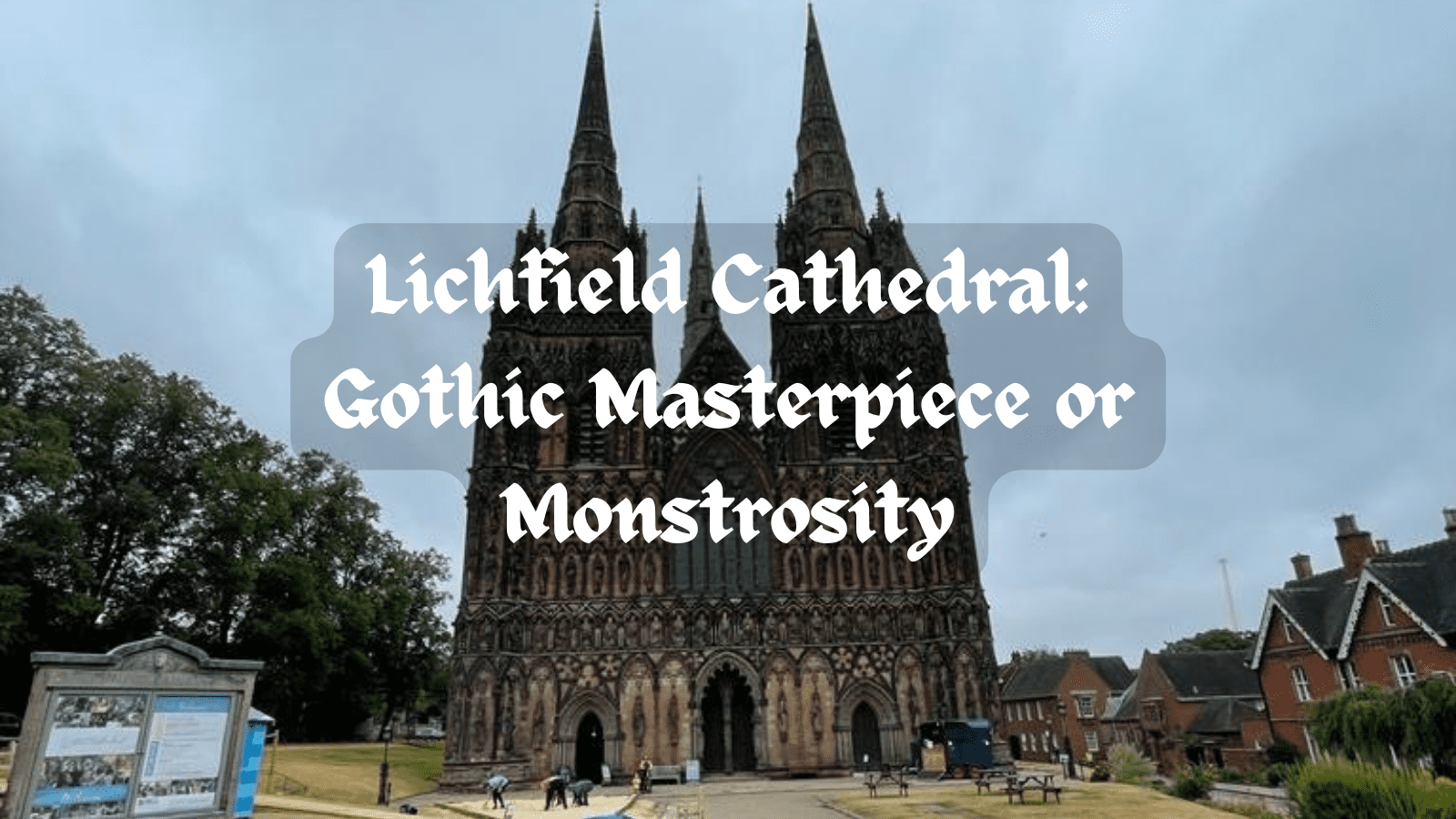

Lichfield Cathedral: Gothic Masterpiece or monstrosity

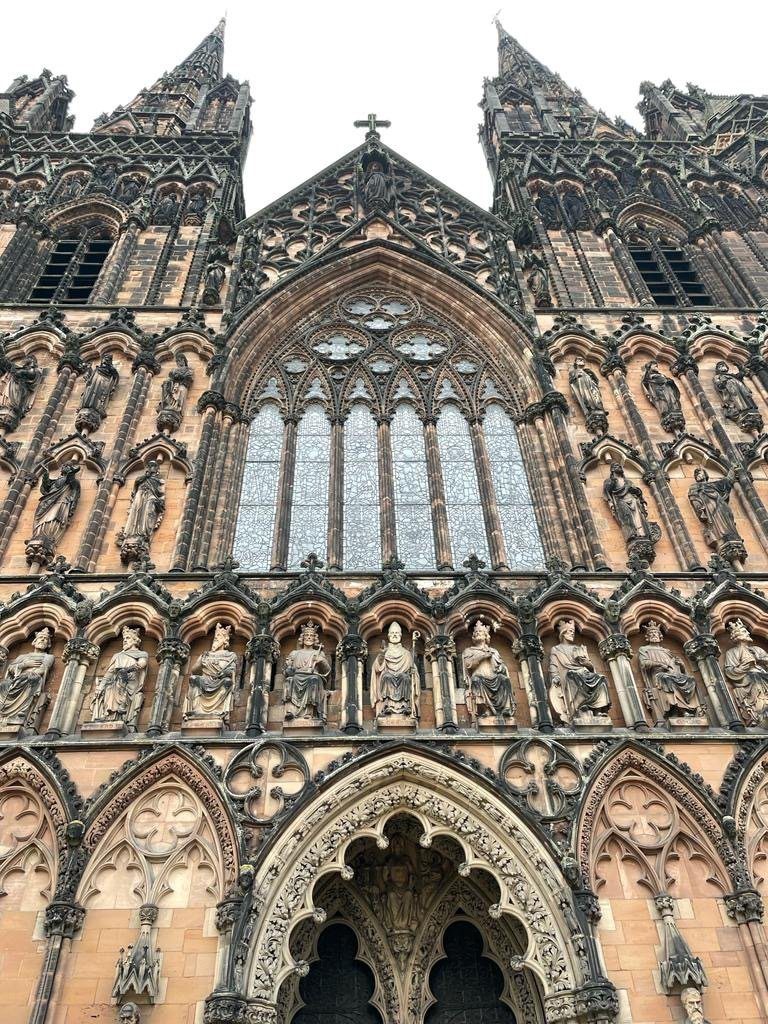

Lichfield Cathedral is dedicated to St Chad and Saint Mary, built from locally quarried sandstone, and consecrated in 700AD. This is the only English medieval cathedral to have three spires, endearing and referred to by the locals as the ‘Ladies of the Vale’.

St Mary’s church stood in the cathedral’s place before, built presumably in 659. The cathedral runs a length of 113 m (371 ft), with its nave 21 m (69 ft) wide. The central spire extends to a height of 77 m (253 ft), and its western spires are around 58 m (190 ft). The weight of the stone in the ceiling vaulting pushes the walls of the nave outwards. Between 200 and 300 tons of stone were removed when the cathedral underwent renovation so that the walls did not succumb to further pressure.

St Chad, the Bishop of Mercia, was Lichfield’s first bishop, taking the position in 669 and moving his see there from Repton. His remains were venerated after his death in 672 and Lichfield became a place of pilgrimage with a sacred shrine housing his bones. He adds to the cathedral’s treasures from St Chad’s tomb chest with the sculpture of the ‘Lichfield Angel’ from the 8th century and the St Chad Gospels that are older than the Book of Kells.

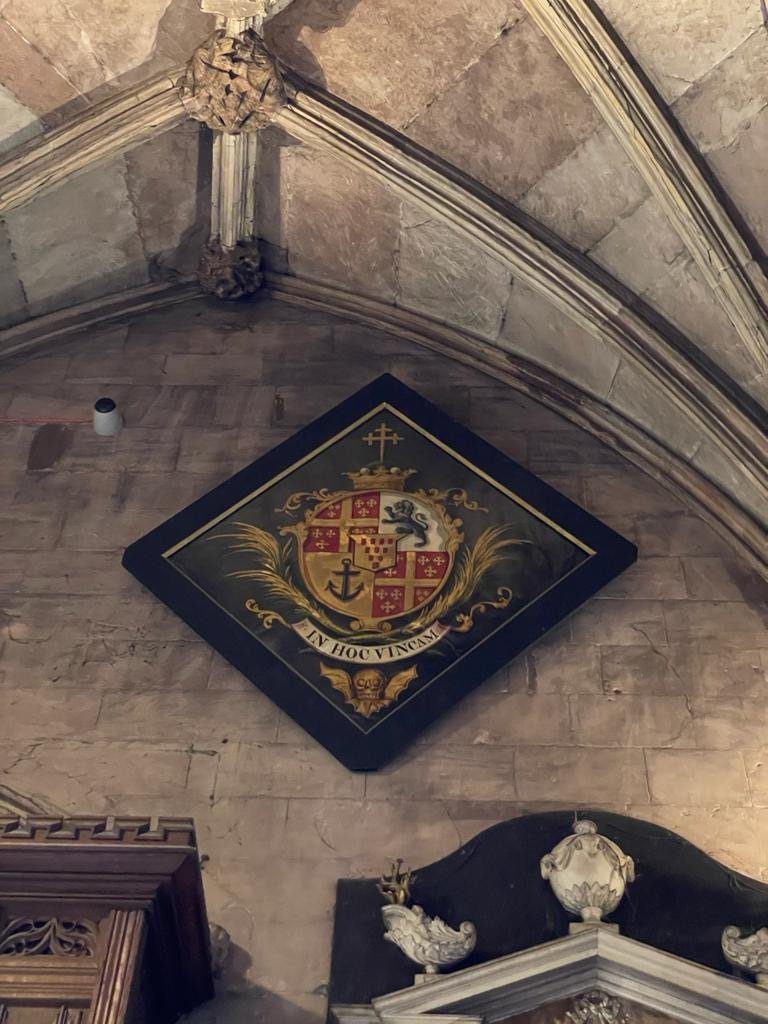

Offa, King of Mercia, created his own archbishopric in 786 in Lichfield as a result of the resentment he felt towards his bishops paying allegiance to the Archbishop of Canterbury in Kent. Pope Adrian seemed to like Offa, and his official representatives supported Offa at the Council of Chelsea in 787. It became known as the contentious synod, and it was here that it was decided that the Archbishopric of Canterbury make way for Offa’s new archbishop despite vehement opposition. Offa and the papal representatives instituted Higbert as the new Archbishop of Lichfield with the support of Pope Adrian. By way of thanks, Offa sent a shipment of gold to the pope every year for alms and to supply the lights in St. Peter’s church in Rome. After only 16 years, however, Archbishop Aethelheard was back in his position as the Archbishopric of Lichfield following Offa’s demise.

Lichfield can boast its place as one of Britain’s oldest centres of Christian worship. After invading the area in 1066, the Normans built a new cathedral in place of the original wooden Saxon church. This was replaced with one built in the Gothic style that was completed by the building of the Lady Chapel in c. 1340. Although sparse remnants of the original Norman cathedral can be seen today, its replacement saw the most damage suffered by any cathedral during the Civil War. This was despite the cathedral close enjoying defensive walls and an encasement within a ditch, making it a natural fortress. The cathedral was victim to three sieges between 1643 and 1646. The cathedral authorities may have sided with Charles I but not the townsfolk who stood with Parliament. In Robert Greville, 2nd Baron Brooke was killed while leading an assault on 2 March 1643. He was killed by a bullet deflected off a shot pulled by John Dyott who was a deaf-mute, positioned on the battlements of the central cathedral spire alongside his brother, Richard Dyott. Brooke’s deputy, John Dell, took over the siege, and two days later, the Royalist garrison surrendered to him.

Just a month later in April, Prince Rupert undertook to recapture Lichfield with a Royalist expeditionary force from Oxford. After Rupert’s engineers breached the defences using what may well be the first explosive mine ever used in England, the parliamentary commander of the garrison, Colonel Russell, surrendered on 21 April.

It was, however, not only parliament that fell. The central spire of the cathedral was destroyed as were the roofs and all the stained glass. The 1660s saw Bishop Hacket use funds donated by the restored monarch to restore the cathedral. Restorations following the Civil War were however only fully completed in the 19th century. The colossal figure of Charles II created by William Wilson stood between the two spires on an ornate gable up until the 19th century, whereupon it was relocated to just beyond the south doors where it stands today.

The Lichfield Angel remained hidden until February 2003 when it was discovered under the nave of the cathedral. This 600mm tall eighth-century sculpted panel of the Archangel Gabriel carved from limestone formed, rumour has it, the stone chest interring the relics of St Chad. It took another 3 years before the Angel was unveiled to the public. The Lichfield Angel took a brief 18 months respite to be examined in Birmingham before resuming its rightful place as an exhibition piece in the cathedral.

Sir George Gilbert Scott restored the cathedral in the Victorian era to the one we know today. But before this, the 15th-century library was pulled down on the north side of the nave. All the books were relocated above the Chapter House, where they remain to this day. The west front saw most of its statues gone, and Roman cement was applied to the stonework. James Wyatt instigated major structural work, adding a stone screen at the entrance to the Choir and making a single worship area of the Choir and Lady Chapel by taking away the High Altar. Francis Eginton was commissioned to work in the cathedral, having painted the east window.

So what was George Gilbert Scott responsible for doing? He saw to the extensive renovations of the ornate west front, including the ornate carvings of kings, queens, and saints in original materials wherever possible. When not possible, new imitations and additions were created and the years between 1877 and 1884 saw new statues filling the empty niches on the west front. Most of these were carved by Robert Bridgeman of Lichfield. The statue of Queen Victoria on the north side of the central window was carved by Princess Louise, the queen’s daughter.

Scott reinvented Wyatt’s choir screen to create the clergy’s seats in the sanctuary. It was replaced by a metal screen designed by Scott and, along with the fine Minton tiles in the choir, are celebrated examples of High Victorian art.

Lichfield Cathedral is the site of three ancient burials, discovered during Kevin Blockley’s archaeological investigation in the Chapter House. The floor of the Chapter House was built in the 1240s, so the two skeletons just under the floor must have been there for some 750 years. Kevin Blockley, the church archaeologist, assumes the burials to be Christian, lying as they were east to west, and in shrouds rather than in coffins. The skeleton of the adult male was removed and inspected but the second skeleton has been left undisturbed. The third was the remains of an infant of high status within the medieval community of its time. It was reburied after being disturbed during the Victorian renovations.