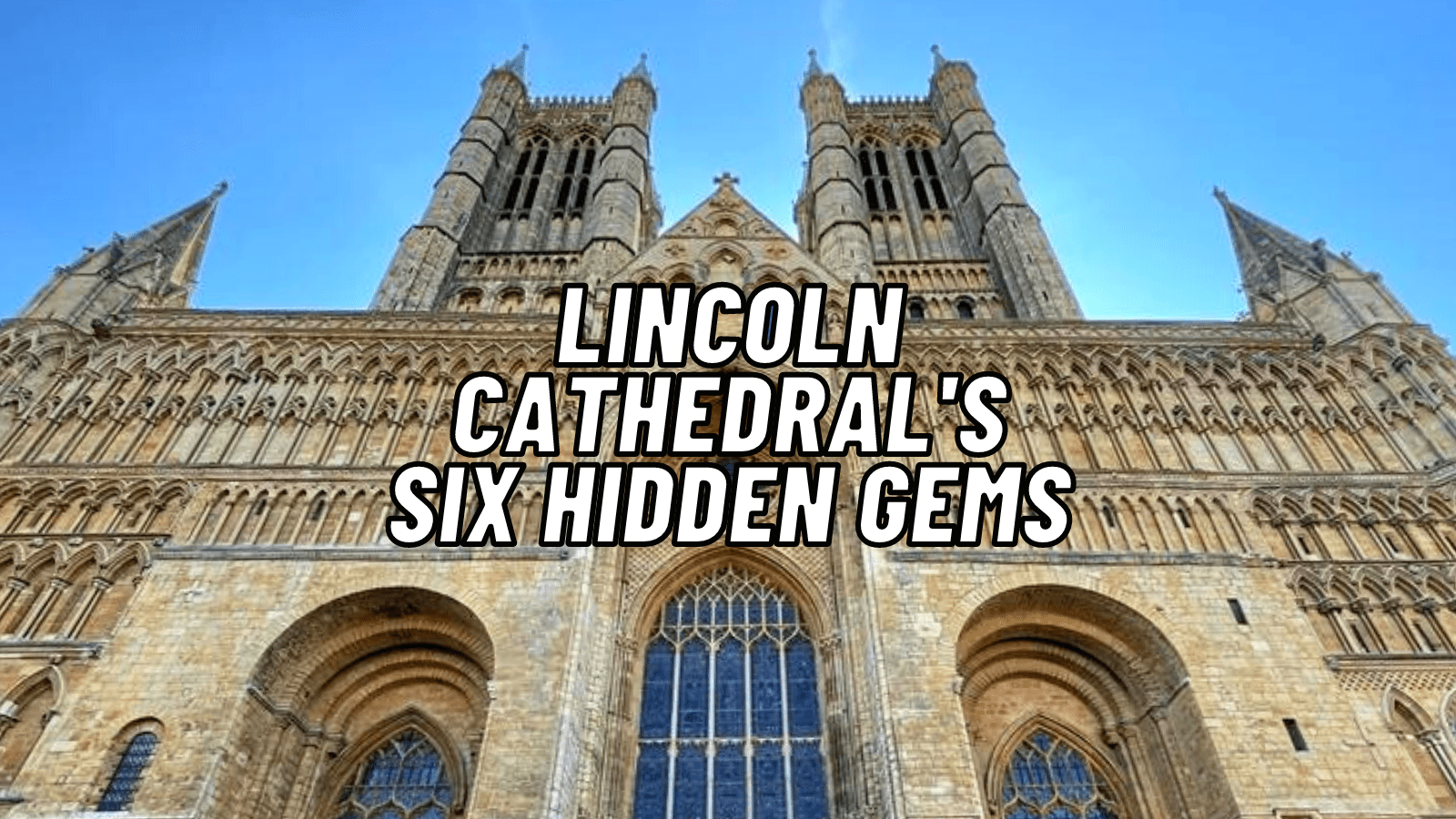

Lincoln Cathedral’s Six Hidden Gems

Lincoln Cathedral is truly a magnificent sight. Built on top of the hill across the square from Lincoln Castle, it dominates the city skyline. Tourists flock to it from across the world. Those who brave the climb up Steep Hill are rewarded with a wondrous sight.

Forget the fact that Lincoln Cathedral was once the tallest building in the entire world. Forget the famous imp that is almost impossible to spot unless you are exceedingly eagle-eyed. Forget that the Cathedral contains the visceral tomb of Eleanor of Castile, the Queen of Edward I. These are the facts and sights that Lincoln Cathedral is famous for. These things draw the tourists in to visit nine hundred years after its completion.

However, Lincoln Cathedral has many hidden gems and stories that the casual visitor often overlooks.

It is these hidden gems that make Lincoln truly stand out as one of the most spectacular historical cathedrals in the world.

The Shrine of Little Hugh

In terms of hard-to-spot monuments within the Cathedral, Little Hugh’s shrine is the toughest. It is located in the South Choir, and quite frankly, it is easy to walk past. Most people would assume it was nothing more than a bench or an architectural anomaly.

These days, it’s a little more than a stone box-shaped sarcophagus. The impressive shrine that was built around it was destroyed during the dissolution.

The story of Little Hugh is truly horrific. It highlights a terrible period in the Cathedral and the city’s history.

In 1255, Lincoln had a budding Jewish community. However, that year, a small boy called Hugh was found dead in the city. He was found in a well after being missing for a month. The population of the city cried, “Murder.”

Rumours began circulating that the Jewish community was to blame for the death.

There was no evidence to support that whatsoever. However, the rumours grew, resulting in 92 Jews being arrested and taken to London, where they were imprisoned in the Tower of London. Eighteen of them were hanged to death.

At this point, the church decided there was money to be made. So the boy’s tomb was put into the Cathedral, and a shine was constructed around it. Pilgrims were encouraged to visit the shrine and leave offerings.

In short, the Cathedral profited from the boy’s death and the unjustified executions of 18 Jews.

Anti-Semitism was a massive problem in England at this point. In 1290 Edward I banished Jews from England, and it took until 1656 for them to legally be allowed to return.

Chaucer mentions the incident in “The Prioress’s Tale.”

The tomb of Little Hugh is easy to miss but is one of the most poignant places in the entire Cathedral.

Today, the Cathedral openly acknowledges its shameful part in this horrific incident.

The Trondheim pillars

The Cathedral obviously has many huge stone pillars (It would fall down without them), but there are two that are different from all the others.

The first is located at the corner of the north choir and the northeast transept, just next to the Treasury.

It is decorated with curling leaf shapes, which are known as crockets. These illustrate the inner column.

Another similar pillar is where the south choir aisle meets the Southeast Transept.

These two pillars are different from every other in the entire Cathedral.

In fact, these pillars are almost unique in the entire world.

The only place similar pillars are found is in Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim, the most northern medieval Cathedral in the world.

The stonemason’s marks on both pillars suggest that they are the work of the same person or the same group of stonemasons. These pillars were constructed in the early 1200s. They show that skilled stonemasons were in huge demand across the entirety of Europe and travelled extensively for work.

Katherine Swynford’s Tomb

Reading down the list of popular things to do in Lincoln Cathedral, you will probably see that Katherine Swynford was buried here. However, her tomb is easy to bypass. It looks very insignificant considering her position in English history.

Katherine Swynford was the long-term mistress of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Gaunt was the third son of King Edward III. He was one of the country’s most powerful and wealthiest nobles and was responsible for constructing famous architectural gems such as Kenilworth Castle.

Katherine Swynford’s relationship with Gaunt probably began when she became governess to the children from his second marriage. Gaunt and Katherine had three children together out of wedlock. When Gaunt’s second wife died, he married Katherine Swynford. The King allowed the line of descent from Gaunt and Swynford to be legitimised.

The surname that was granted to those children was Beaufort. That line ultimately ended with Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry Tudor, the future Henry VII. It was through Margaret Beaufort that the Tudors had their “claim” to the throne.

However, there was a problem with the Tudor claim to the throne. One caveat was attached when the Beaufort line was legitimised – the Beaufort line could never claim the crown of England. So, the Tudor claim to the throne was weak from the very start.

You will note that Katherine Swynford’s tomb has had its brass markers and effigies removed. Those brass images were removed by parliamentarian forces during the English Civil War and used to make weapons. They didn’t just stop at Swynford’s tomb. They desecrated the entire Cathedral. Ultimately it made the identification of the tombs and grave markers somewhat tricky.

The Gallery of Kings

Before you even enter the Cathedral, there is something that’s often overlooked by the visitors, who are usually in awe of the sheer size and scale of the building and are keen to get inside.

They forget to look over the large West Door.

There are life-size statues of English kings. They are meant to depict William the Conqueror all the way through to King Edward I. In many ways, it is similar to the Kings Screen in York Minster, albeit only going up to Edward I and not Henry VI.

The Tomb of Bishop Richard Fleming

Richard Fleming was the bishop of Lincoln between 1420 and 1431. It was he who founded Lincoln College at the University of Oxford.

However, outside of the alumni of Lincoln College, the name of Richard Fleming is probably unknown. But his tomb in the North choir aisle is undoubtedly worth visiting.

He is depicted twice upon it.

At the top, he is in his bishop’s robes and mitre, looking very much as he would have done in the prime of life.

However, below is a depiction of his cadaver – wasted away as nature took his course.

He is one of the very first cadaver-style tombs in the country. They are meant to act as a reminder that even the great and the good die and revert to ashes like the rest of us.

The Chapter House

The chapter house is located along the cloisters. It is a ten-sided structure, and its construction began in the 1220s. A huge stone pillow in the centre supports 20 ribs that fan out into the vaulted roof.

This chapter house is significant because no less than three parliaments were held within its walls.

King Edward the first house of Parliament in Lincoln in 1301. Edward II did the same in 1316. In 1327, King Edward III, who was a child of the time, announced at his own Lincoln Parliament that his disposed father, Edward the Second, had died while imprisoned in Berkeley Castle. Of course, died is far too soft a term, as it is believed that Edward II had been murdered.

The Chapter House features three parliaments in the story of the Knights Templer. During their downfall in 1310, 11 Templars were interrogated within the chapter house. After their interrogations, they were transferred to London to await their fate.

Finally, the last great historical significant event that occurred in the Chapter House happened during the reign of Henry VIII.

The rebels from the Lincolnshire rising met here while they waited for an answer to their demands from the king. They weren’t pleased with Henry VIII’s response.

Hearing that he was sending a military force, they immediately dispersed.