The death of Henry VIII: A pitiful end

Henry VIII died on the 28th of January 1547 at Whitehall Palace in London. He was aged 55. Technically, he died of natural causes. However, he suffered from severe obesity, an open ulcerated leg, and had, within the last eleven years, suffered from massive head trauma from his infamous final jousting accident. There is a high probability that the king suffered from type two diabetes and other obesity-related illnesses.

Henry’s final months were filled with paranoia, manipulation, and tyranny.

When he came to the throne aged just 17, Henry was welcomed as a virtuous prince. However, after going through six wives and executing in the region of 72,000 people during his reign, he gained his place as the most infamous monarch to sit on the throne.

Much of what Henry accomplished in his life remains overshadowed by the executions and the cruelty.

Henry’s decline in health wasn’t rapid. It had its groundings eleven years before his death.

The slow decline of Henry VIII

Henry suffered his last infamous jousting accident in January 1536. He was unseated from his horse with a lance blow, the horse itself fell on top of him, and he was unconscious probably for a matter of hours. The severity of the jousting accident was that many in his inner circle believed the king would never recover and he would shortly die. However, recover he did.

But it wasn’t a complete recovery. Henry suffered massive head trauma. Today, medical professionals believe this changed his personality and drove him to the tyranny that he is often associated with. In addition to the head injury, Henry also suffered injuries to his leg. This would result in open ulcers forming for the rest of his life. Over the next 10 years, Henry would survive more than one occasion where the infection in his legs risked his life.

The apparent injuries from the jousting accident were probably not the most significant factor in his decline. The once active and exercise-loving king could no longer partake of his favourite pastimes. The long six-hour hunts, tennis games, and of course, the jousts became a thing of the past. However, Henry’s massive appetite didn’t moderate in line with his reduced activity. As a result, his waistline increased. At the time of his death, it was estimated that the king probably weighed more than 25 stones.

Due to Henry’s rich diet and obesity, he probably suffered from untreated Type II diabetes. However, this cannot possibly be substantiated.

Henry’s struggles

After Henry’s victory at the siege of Boulogne, his health took a marked turn for the worst.

The weight seemed to pile on quicker. As a result, his activity level decreased. It became a vicious cycle.

Henry’s paranoia increased as he battled against the two warring religious factions on either side of his council. He had the traditionalists in one corner, with Bishop Stephen Gardiner at the head supported by the Duke of Norfolk, his son Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey. On the opposing side for the reformers. The leaders of this faction were the influential Seymours, Dudleys, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, and, albeit somewhat less open in her views, Queen Catherine Parr.

Henry came to believe that everyone was out to get him. His paranoia increased as he played both parties off against each other with increasingly regular occurrences.

The traditionalists believed they had won the battle when Henry agreed to draw up an arrest warrant against Catherine Parr to examine her supposedly heretical views. However, the warrant was never served as Catherine and Henry were reconciled after she submitted to his views and vowed never to question the king again.

Henry’s final speech to Parliament

Henry was no longer the powerful figure that he once was. For those in his inner circle, the myth around his invincibility all but vanished. Over time, various measures were introduced to account for the king’s failing health. Wheelchairs were constructed to move Henry around his palaces. Lifts were installed in them to winch Henry up to the upper levels in secret. Those that saw him daily knew that he was a broken man, a shadow of his former self.

However, a little more than a year before his death, Henry attended Parliament on Christmas Eve 1545 and delivered an address.

It was Henry at his finest. A throwback to the charismatic prince of his youth.

It was a bombastic display that combined a mixture of chastisement, humility, and praise for both his audience and the general population.

He berated the clergy for the lack of unity.

“I must needs judge the fault and occasion of this discord to be partly by the negligence of you, the fathers, and preachers of the spirituality… I see and hear daily, that you of the clergy preach one against another, teach, one contrary to another, inveigh one against another, without charity or discretion. Some be too stiff in their old mumpsimus, other be too busy and curious in their new sumpsimus. Thus, all men almost be in variety and discord, and few or none do preach, truly and sincerely, the word of God, according as they ought to do. Shall I now judge you charitable persons doing this? No, no; I cannot so do. Alas! How can the poor souls live in concord, when you, preachers, sow amongst them, in your sermons, debate and discord? Of you they look for light, and you bring them to darkness. Amend these crimes, I exhort you, and set forth God’s word, both by true preaching, and good example-giving, or else I, whom God hath appointed his vicar, and high minister here, will see these divisions extinct, and these enormities corrected, according to my very duty, or else I am an unprofitable servant, and an untrue officer.”

He called for the country to come together in good Christian charity.

“I am very sorry to know and hear how unreverently that most precious jewel, the word of God, is disputed, rhymed, sung, and jangled in every alehouse and tavern, contrary to the true meaning and doctrine of the same; and yet I am even as much sorry that the readers of the same follow it, in doing, so faintly and coldly. For of this I am sure, that charity was never so faint amongst you, and virtuous and godly living was never less used, nor was God himself, amongst christians, never less reverenced, honoured, or served. Therefore, as I said before, be in charity one with another, like brother and brother; love, dread, and serve God (to the which I, as your supreme head, and sovereign lord, exhort and require you); and then I doubt not, but that love and league, which I spoke of in the beginning, shall never be dissolved or broken between us. And, as touching the laws which be now made and concluded, I exhort you, the makers, to be as diligent in putting them into execution, as you were in making and furthering the same, or else your labour shall be in vain, and your commonwealth nothing relieved.”

Key events of the year 1546

The final full year of Henry VIII’s life had the occasional high spot.

The first was the visit of the French Admiral to unify the recently agreed treaty between the two nations. Throughout the stay, Henry was in fine form, and the Queen and his children played prominent roles in the celebrations.

Then in the autumn, Henry went on his final royal progress with Catherine Parr. It was a short affair compared to some of his other progress and was convened to the country’s south. It was a final flourish of fun for the king.

By the time of the royal progress, the reformers on the council were firmly in the ascendancy. Bishop Stephen Gardiner was refused an audience with the king. On the 13th of December, the Duke of Norfolk and his son, the Earl of Surrey, were arrested and taken to the tower.

It was clear that after the king’s death, more significant religious reforms would take place.

In mid-December, Henry suffered a short illness believed to have been linked to the condition of his legs; however, he rallied quickly.

Clearly, Henry knew that his end was rapidly approaching, and he needed to make arrangements for after his death. He decided to send the Queen and his daughters away to Greenwich for Christmas. The court that remained at Whitehall consisted of just the privy council and his very closest gentleman of the chamber.

The final chapter in Henry VIII’s extraordinary life was about to play out.

Henry VIII’s final month

On the day after Christmas 1546, Henry VIII called for his will. When Sir Anthony Denny read the document aloud, Henry declared it not to be the document in question. He insisted there was another will written later in the hand of the Lord Chancellor. The correct copy was located and read out.

The contents of Henry VIII’s will have always been open to speculation. By this point in his life, he had ceased to sign documents. Instead, a stamped version of his signature was used to authorise all manner of documents from the mundane through to execution warrants. It makes the contents of his will somewhat debatable. Was the document doctored by a person or persons unknown and then duly stamped with Henry’s signature?

Henry decided he was going to make some corrections to the document as it stood. He removed Stephen Gardiner from the list of executors and counsellors who would advise his son.

After this point, it was merely a matter of time. Everyone knew that Henry was dying. His council were starting to make the preparations quietly and discreetly for the transfer of power.

No one other than the privy council had access to Henry VIII’s chambers. Not even his wife or his daughters, who were all desperate for news. By early January, rumours were circulating around the court the king was already dead. However, these rumours were silenced when Henry received both the Imperial and French ambassadors on the 16th of January.

On the 19th of January, the Earl of Surrey, Henry Howard, was executed for treason. He was beheaded on Tower Green. Henry VIII had become paranoid that Howard was attempting to seize the throne from his son, Edward, after his death. He became Henry VIII’s final victim.

On the 27th of January, royal assent was given to the attainder of the Duke of Norfolk. His execution was scheduled for the 29th of January.

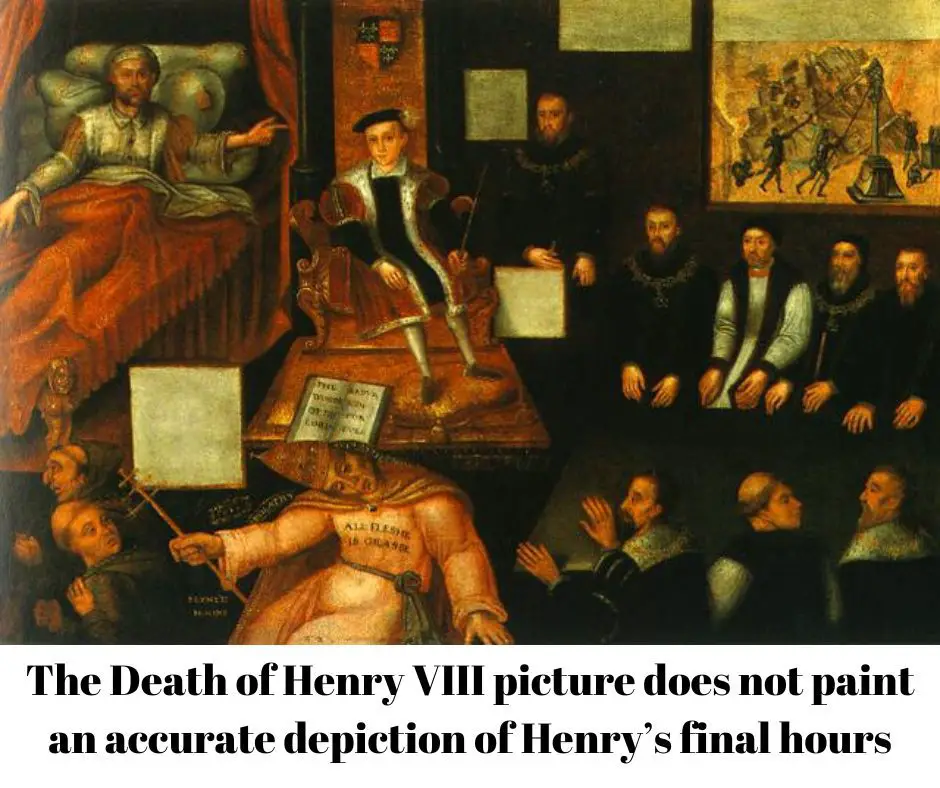

However, by this point, Henry VIII was on his final decline. Finally, Sir Anthony Denny told the king that he was dying and that he should prepare his soul for his final journey. When asked who should he send for, Henry declared that it should be Cranmer but would take a little sleep before finally deciding.

By the time Cameron was summoned and reached Henry’s bedside, the king could no longer speak. When asked if he died in the faith of Christ, Cranmer confirmed that the king had squeezed his hand.

Henry VIII died quietly in the early hours of Friday, the 28th of January 1547.

A pitiful end for a once-powerful figure.

The subterfuge after Henry VIII’s death

The king’s death wasn’t publicly announced for three days.

During that time, all of his meals were brought into the chambers to great fanfare.

All while the dead king’s body began to rot.

Edward Seymour, Lord Hertford was busy securing the body of the new King, Edward VI.

Within a matter of days, the provisions in Henry VIII’s will were ignored. As opposed to a council of equals to manage the regency of the nine-year-old Edward, Lord Hertford was made Lord Protector, essentially king in all but name.

The plans that Henry had for a grand tomb came to nothing. None of his three children bothered to finish the project when they came to the throne. Henry remained in his unmarked grave next to Jane Seymour in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle.

Many feel aggrieved that Henry had a peaceful death, warm in bed after inflicting so much suffering to others.

When told by Denny that he was likely to die, Henry said he believed that Christ in all His mercy would ‘pardon me all my sins, yea, though they were greater than can be.’

It is a big question. Would Henry’s sins have been pardoned?